OUR STORY

By Zongfu Yu

Things were about to get much slower.

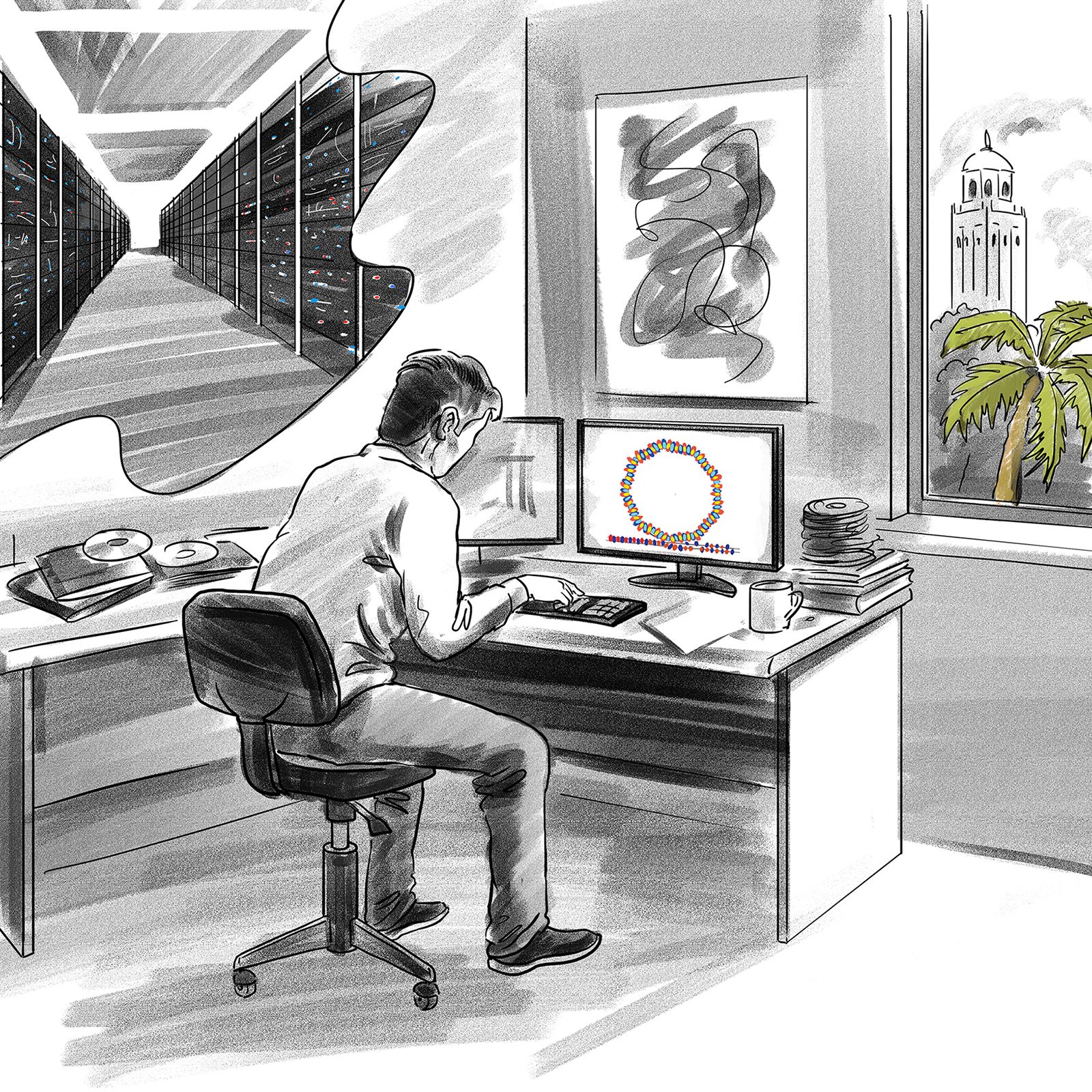

My thesis was to develop silicon optical isolators. An isolator is a device that functions like a one-way valve for light. Without it, people could not fully leverage the power of modern semiconductor facilities to build next-generation optical communication chips. After working out some initial designs, it became clear that I needed massive computing power to validate those ideas. The computing involved solving large-scale Maxwell’s equations to simulate the physics of light propagating on a silicon chip. It required a megawatt supercomputer. However, there were not many megawatt computers in the entire world.

My thesis was to develop silicon optical isolators. An isolator is a device that functions like a one-way valve for light. Without it, people could not fully leverage the power of modern semiconductor facilities to build next-generation optical communication chips. After working out some initial designs, it became clear that I needed massive computing power to validate those ideas. The computing involved solving large-scale Maxwell’s equations to simulate the physics of light propagating on a silicon chip. It required a megawatt supercomputer. However, there were not many megawatt computers in the entire world.

A long journey began. My Ph.D. advisor Shanhui Fan, who later became my co-founder, needed to convince the National Science Foundation to allow us to use one of their very few powerful supercomputers. He sent in a 5-page proposal. After a few months waiting, I got my password, delivered through postal service. The next step was to compile the code developed by previous Ph.D. students. I could smell the dust that the code had collected while stored in an external harddrive for years. Compiling it on a supercomputer was like reviving a roadkill squirrel. It took weeks before I could get it to work.

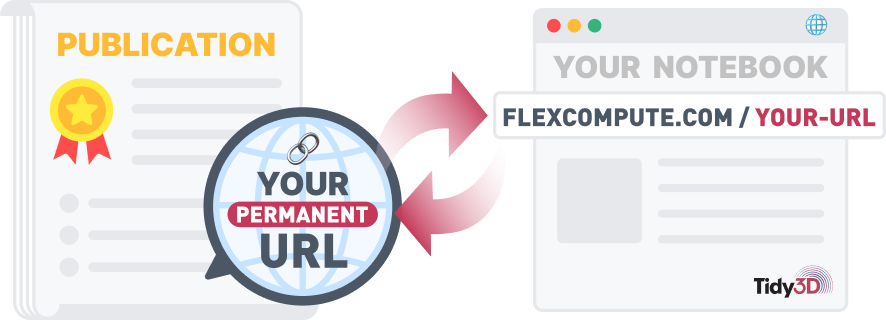

When I thought I was finally ready to conclude my study with just a few big simulations, it was actually the beginning of a two-year long effort. The computing jobs submitted to the supercomputer would wait for days or even weeks. As a result, I could only iterate my design once a week. It would be after 50 iterations and almost 2 years before I finalized an isolator design. Then I graduated with the work published as the cover story in a pretty good journal. At the time, it didn’t bother me much that the speed of innovation was bottlenecked by a computer rather than by my brain power. While the productivity was painfully low, I took it as the cost of doing research.

Ten years later, in 2015, I was already an engineering professor at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. I relived the same experience again. The difference was that my graduate students would be patiently waiting for computing. This time, it really bothered me because it turned out that watching my graduate students waiting for computing is a totally different experience than waiting for computing myself as a graduate student. Ten years ago as a graduate student, I didn’t have to worry about the cost of payroll and a ticking tenure clock.

Later that year, I went to Boston to visit my longtime friend Qiqi Wang, an engineering professor at MIT who later became my co-founder. I was checking Instagram on my iPhone in an Uber when I had a sudden realization: none of these existed 10 years ago. Over time, business computing had brought innovations that made daily life more convenient – yet engineering computing had stagnated. We – the engineers who design new gadgets in the physical world– seemed to live in a world that had been forgotten by Silicon Valley entrepreneurs. We also need innovation in order to innovate faster! If no one would build new computing tools for us, we should roll up our sleeves and do it for ourselves.

Months later, Qiqi, Shanhui and I founded Flexcompute with one mission: using advanced computing to accelerate innovation. We were fortunately joined by a group of exceptionally talented friends who became Flexcompute’s early team.

Today, our computing technology is helping hundreds of university researchers from Yale, Purdue University, Columbia University, Boston University, University of Wisconsin, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, MIT, Stanford University and many other universities around the world. We are also proud to support dozens of companies to design their electric cars, electric aircrafts, high-efficiency wind turbines, and quantum computing chips. Simulating the physical world by solving massive differential equations allows them to design better and more efficient products. With Flexcompute they simulate an airplane in 5 minutes, instead of 10 hours before; a quantum circuit in 3 minutes, instead of 20 hours before. Our customers have never been able to iterate their designs so quickly. But this is just the beginning of a new era of engineering computing.